Reading Sara Ahmed: A Memo on Feminism and Affect Theories

This article is my summary and thoughts on Sara Ahmed’s (2006) “Orientations: Toward a Queer Phenomenology.”

The first thing I want to note is that this article makes me uncomfortable when I’m near any of my tables, such as the one I’m using now, my desk.

In this article, Sara Ahmed (2006: 543) adopts the concept of “orientation” from the tradition of phenomenology to queer studies, offering a new approach to organizing key themes in queer theory: the body, sexual orientation, and queer politics. First, one might ask, “Why phenomenology?” Ahmed (544) explained that phenomenology emphasizes the importance of lived experience, the intentionality of consciousness, the significance of nearness or what is ready to hand, and the role of repeated and habitual actions in shaping bodies and worlds. Although she used the following sections to discuss these goals respectively, Ahmed stopped her explanation here, as if everyone could see the connection between these goals of phenomenology and the goals of feminist theories (lol). I would try to use some examples I’ve learned to bridge the phenomenology to feminism. First, feminists care about the lived experience, as the Combahee River Collective (1977) stressed in their collective statement, identity and personal experiences matter, because that’s where we start our political actions. Raising this discussion to the epistemological aspect, Donna Haraway (1988) has pointed out that all knowledge is produced by a person situated in a specific social context, from a partial sight. Hence, body matters; vision matters; situation matters. Our position will affect what things are nearer to us, what things are more reachable, which is a key theme of the phenomenology discussed later. Finally, repeated and habitual actions are closely related to feminist issues, such as how we do gender (West and Zimmerman 1987), how gender is performed repeatedly, and ultimately becomes something “real,” something we can identify with (Butler 1990). This is the famous process we refer to as the “social construction” of gender. Hence, phenomenology is an ideal theoretical approach for discussing these prominent feminist issues, as its core focus encompasses many crucial feminist debates.

So, how do phenomenologists discuss orientation? First, the starting point matters. Because where we start is the reason why differences from this side to that side matter, and how we determine what things are nearer, more reachable to us. The starting point is where the world unfolds. Additionally, I would like to highlight that we can connect the emphasis on the starting point to feminists' focus on the situation (de Beauvoir 1949/1953, Haraway 1988). Second, direction matters. Ahmed (546-547) wrote that what we can see at first depends on which way we’re facing. The objects that we direct our attention toward reveal the direction we have taken in life. If we face this way or that, then other things, and indeed spaces, are relegated to the background, which leads to our third point: background matters. Ahmed (549) extended Husserl’s discussion of background, arguing that two meanings of background should be considered: the spatial one and the temporal one. For the spatial meaning, it highlights which part is situated in the rear. For the temporal meaning, we could see the history of how one thing arrives here and is perceived by us. In sum, when discussing orientation, our starting points, and in which direction we project our attention toward matter, because it will impact what thing is the object of our perception and what’s the background. In addition, when we say background, we not only mean the rear side, the side that we can’t see of the object we’re facing, but also the history of its arrival.

I’ve highlighted the importance of distance subtly above; now, let’s dig into it. The object that philosophers were observing, such as THE table, could be described in two ways. First, intuitively, it’s a thing in space, as a spatial thing. However, as Heidegger argued, this is not enough. Because what makes THE table what it is, and not something else (not just A table), is what the table allows us to do. It’s the characteristics of the being, which is another way of description. Hence, we can see that the contexts surrounding the object will impact the existence of the object we’re depicting. At the same time, our bodies are not just another object in the world, as Merleau-Ponty showed, they are our point of view in the world, our starting point. The proximity between the body and objects determines which objects can be touched, through a process in which the body and the object shape each other. Bodies, as well as objects, take shape through being oriented toward each other, because an orientation that may be experienced as the cohabitation or sharing of space.

Now we have not only the intimacy of co-dwelling but also the importance of where we’re orienting toward. In Ahmed’s words, orientations are about the directions we take that put some things and not others in our reach (552). Here is another thing that matters: what’s reachable. What’s reachable depends on our horizon, which will also decide what we cannot reach. Our horizon is bodily, and our bodily horizon is sedimented histories. The vector of temporality is essential because what we can reach does not only depend on our spatial horizon, but also on what has happened in the past, the historical accumulation. One concept that’s helpful for our understanding of sedimented histories is “path dependence” from the tradition of historical sociology. What’s around us is not only decided by our physical horizon, but also our path along the way from our starting point. Every decision we made in the past will make something more reachable to us now, while others will remain relatively unreachable. Eventually, the repetition of history will take us to certain conditions. In addition, the direction we’re heading toward will also come into view as we take steps to bring ourselves much nearer to our goals. So, our presence is constituted by our past (the path we’ve been treading on) and our future (our orientation). Ahmed (553) summed up these ideas delicately in these two sentences: Bodies tend toward some objects more than others, given their tendencies. These tendencies are not originary; they are effects of the repetition of “tending toward.”

Now, let’s apply these ideas around orientation to the discussion of sexual orientation. As Simon de Beauvoir pointed out, one is not born but becomes straight. In this view, we’re born at the starting point; then we’re forced to treat heterosexuality as our goal; then, through the repetition of tending toward heterosexuality, we inherit the path given by society, and then reproduce this path by treading on it. This force is known as “heteronormativity.” We inherit it from our family, and by following this line, we reproduce this line. The line is represented in our family tree, which consists of several horizontal lines (representing siblings and spouses) and vertical lines (representing parents and children). Parents used force to keep their children “in line,” making children must orient themselves toward the opposite sex as loved objects. When we’re inheriting a particular line, we also inherit the proximity of certain objects, like materials, values, capitals, aspirations, projects, and styles. Thus, objects around us are distributed unevenly. The possibility of reaching every object varies: some options are more likely to occur, while others are not. The force from the parent or the broader society, the so-called heteronormativity, presents as a form of demanding (asking an opposite sex partner) and prohibition (banning a same sex partner), both of which are generative. According to Foucault’s analysis, prohibition is a generative action that creates objects and worlds. Actively sweeping some objects away is a way of world-making, too, since it impacts what things can coincide.

In this sense, heteronormativity could be considered as a background, with its spatial and temporal aspects, asking for a specific direction (heterosexuality is the orientation) to happen repeatedly. During the repetition, some objects will stand out and gather while others remain distant. For example, a bright heterosexual family life could be represented by the actual gathering of the family or even just a collection of family pictures, in which specific images will stand out to the viewer. Hence, heterosexuality is not simply an orientation toward, but something we’re oriented around. In this sense, the compulsory heterosexuality Andrienne Rich had coined is not turning away from queer objects and accepting heterosexual objects, since what’s considered queer might be removed or remain invisible, unreachable in the first place.

After discussing the “straight line,” Ahmed shifted toward the queer slant. As mentioned above, heteronormativity tends to direct our attention toward certain objects, rather than others. Ahmed (560) called it “straight tendencies,” which will make the queer body become a failed orientation. However, the slant of queer body will not last very long. Merleau-Ponty provided us with a good example to understand this “straightening” process: if we ask a man to see the room only through a mirror placed at a 45-degree angle to the vertical, he will first perceive the room as slanted. Things around him will look obliquely, during which time we name as “queer moments.” However, after a few minutes, all things will become vertical for him again. Ahmed (561) referred to this mechanism as “reorientation.” Bodies will tend to straighten up the space because they want to extend into space. Queer moments must be overcome not because they contradict the governing law, but because they block bodily action, which means the body will cease to extend into phenomenological space. Ahmed (562) employed the concept of reorientation to describe heteronormativity, viewing it as a mechanism for straightening. Ahmed provided a story that is helpful for comprehension: her neighbor saw her partner, who I guess is a woman-like person, before the day she came across Ahmed. The neighbor asked Ahmed, “Is that your sister or your husband?” In this case, the queer moment occurred when her neighbor saw Ahmed and her partner, a couple of lesbians. This scene is oblique to the straight line, which prevents her neighbor’s body from extending into this phenomenological space. Hence, her neighbor tried to “reorient” what she saw toward the straight line: first, she considered her partner as her sister; then, she considered her partner as her husband, even though her partner is not even a male. In this case, we see how the lesbian couple was first oblique and not understandable, but soon, they are forced into two “straight” categories: siblings or husband and wife. Hence, orientation is about alignment between space and bodies. Spaces are oriented around straight bodies, which allow those bodies to extend into space (563).

As we can see now, orientation is essential. We cannot replace the “sexual orientation” with “sexuality” just because the former centers the relation between desire and its objects. Orientation affects what the body can do: it’s not that the object causes desire but that in desiring certain objects, other things follow, because this is how the social is already arranged (563). Our sexual orientation, the sex of our object choice, affects what we can do, where we can go, how we’re perceived, and so on.

Now, let’s import the temporal dimension into our discussion of homosexual orientation. First, it takes time to become a homosexual person because we need to gather tendencies into specific social and sexual forms. Teresa de Lauretis describes this process as “habit-change.” It takes time and work to inhabit a lesbian body; the act of tending toward other women has to be repeated, often in the face of hostility and discrimination, to gather such tendencies into a sustainable form. As Ahmed (564) stated, that might be the reason why becoming a lesbian can feel like a whole world has opened up. Because the entire world has opened up, you must gather your tendencies into specific forms, and you must create your own world by repeating your tendencies again and again. Hence, desire is productive. In being oriented toward other women, lesbian desires also being objects near, including sexual objects, as well as other kinds of objects, which might not have otherwise been reachable within the body horizon of the social. Lesbian desires enact the coming-out story as a story of “coming to.” This world-making process does not occur in a vacuum or an alternative space, but within the heteronormal space. Hence, we should not romanticize or idealize this process.

Before we move on, I would like to initiate a dialogue among MacKinnon, Spivak, and Ahmed on the topic of desire and sexuality. Through the critics of Deleuze and Guattari’s theory of desire, Spivak (1988: 68) alluded that others must mediate desires, aligning with Lacan’s tradition. While MacKinnon (1989: 128-131) discussed sexuality, she emphasized power defined by men, forced upon women, and constitutive of the meaning of gender. Women are defined by what males desire for arousal and satisfaction, and it is socially tautologous with female sexuality and the female sex. In my opinion, since they all cited Foucault’s analysis, they will both agree with the generative of power. The exercise of power will define where our desires lie. Hence, others mediate our desires, and in MacKinnon’s opinion, others mean men and their desires. However, unlike Spivak and MacKinnon, Ahmed discussed the social process of mediating desire more implicitly. Ahmed mentioned the social forces that compel us to desire particular objects; however, if we add MacKinnon’s idea to this process, we will find that who has more power to influence our tendency is related to gender inequality. Our orientation is defined by men, in my opinion, especially cishet men, and it’s essential to take this unequal power relationship into account.

Since we’re in a space trying to straighten up queer bodies, queer moments are fleeting, too. Here, Ahmed introduced two key concepts to describe the intersection of queer and phenomenology: distance and disorientation. As Merleau-Ponty pointed out, the distinction between “straight” and “oblique” is related to the distinction between “distance” and “proximity.” Distance is lived as the “slipping away” of the reachable, of grip over an object that is already within reach. To be able to lose only insofar as this thing is within my bodily horizon. The straight world makes heterosexual objects closer to us while distancing oblique objects. In addition, this straight world will continue to reorient itself to overcome queer moments. Hence, queer objects and moments are something that slips away. How can we orient ourselves to something, the queer objects and moments, that keeps slipping away? That’s the core of queer phenomenology: orientation toward what slips, allowing what slips to pass, in the unknowable length of its duration.

In contrast to the heterosexual reorientation device, queer phenomenology functions as a disorientation device, as it does not aim to overcome the disalignment, the sexual disorientation, and its subsequent social disorientation. Queer thus becomes a way to inhabit the world at the point at which things fleet. (MIND BLOWN!!!) Before we move on, I want to discuss whether this dichotomy of heterosexual and homosexual fell into the shortcomings described by Cathy Cohen (1997). (AGAIN!? Yes.) In my opinion, these criticisms may be valid if we think that all heterosexuals are following the straight line. As Cohen (1997) pointed out, heterosexual lives are not homogeneous. Lives of welfare queens might be different from the lives of successful cishet male CEO. Hence, it's not wise to lump all heterosexuals together and call anyone left “queer.” However, we first have to notice that the aspect of what Cohen was discussing, that is, how we form queer politics and social movements, is different from Ahmed’s. Focusing on the overlapped topic: queer politics, I think Ahmed will not agree with the tactics of lumping all heterosexuals together. If we extract the key points of Ahmed, that is, there’s an ideal life model this society is forcing you toward, and apply it to a broader context of the social justice movement, it’s possible to include welfare queens in the queer politics. Welfare queens are also failing when society thinks that living independently is the ideal, which is where everyone should orient themselves. Hence, like how queer people are being forced to line up at the same time being excluded from the ideal line, welfare queens are suffering from a similar reorientation/disorientation mechanism, too. Welfare queens are finding their ways and going astray, too. I think Ahmed didn’t explicitly outline how to form a coalition between these lost people in this article, since it's not her central argument.

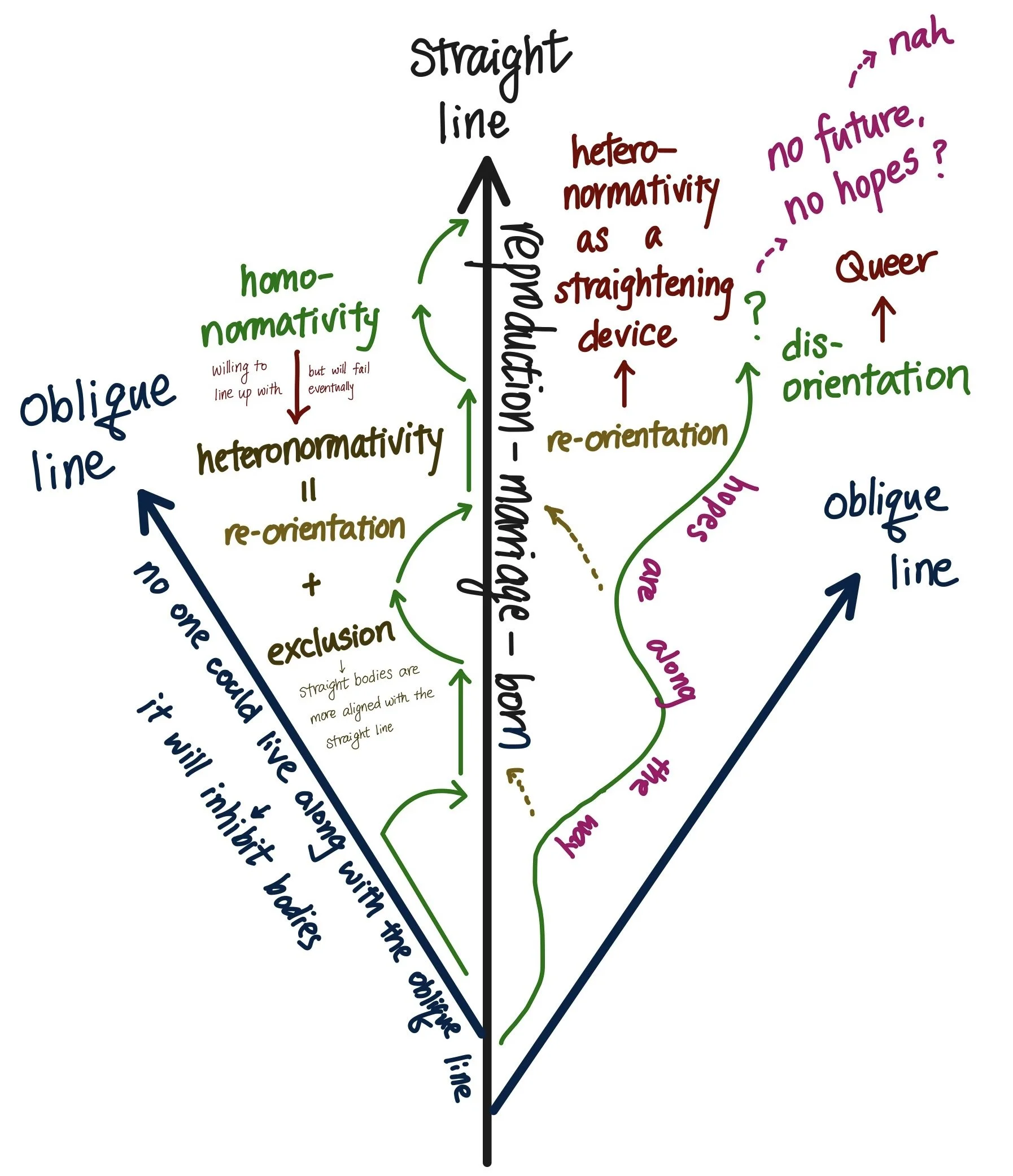

Back to Ahmed, some queer scholars, like Lisa Duggan and Jack Judith Halberstam, have pointed out that lesbians and gays have their own lines, too, which is known as “homonormativity.” Like Bruce Bawer, many queer people are willing to join the big table, the straight line (born-marriage-reproduction-death). Like the figure I drew below, according to Ahmed’s analysis, these relatively conservative queer people, who are embracing the heterosexual ideal of life course, will be willing to be reoriented toward the straight line. However, they will be rejected eventually by the straight bodies, which can and do line up with the straight line. Queer bodies are out of place in specific family gatherings, which is what produces, in the first place, a queer effect.

Illustration of Ahmed’s theory on sexual orientation and queer politics (drawn by me)

So, does that mean we have to keep ourselves always in line with the oblique line? No. As Ahmed (569) emphasized, it is important not to make disorientation an obligation or responsibility for those who identify as queer since it’s demanding and psychologically or mentally impossible and unsustainable. So, queer lives and politics are influenced by disorientation, but it’s impossible to live along the oblique line. As informants from Kath Weston’s ethnographic work on non-normative families noted, constructing kinship in the absence of models can be both difficult and exciting at the same time. Hence, Weston and Halberstam stressed that queer lives are about the potentiality of not following a certain conventional script of family, inheritance, and child-rearing, including not conforming to the disorientation. Queer politics could thus be politics of opening toward the changing direction, finding other paths, or even treading on the path that does not clear a common ground; queer lives could be lives that keep the possibility of going astray. For Ahmed (570), what is important is not finding a queer line but asking what our orientation toward queer moments of deviation would be. What will we do when things slip away? Where can we find support when we feel oblique, strange, and out of place?

Queer politics of finding paths hold hope even without a clear future, as Ahmed (570) suggests. Our hopes are not because of the “not-yet” future, but because of the lines that accumulate through repeated gestures, the lines that gather on skin, already take surprising forms. We have hopes because what is behind us is also what allows other ways of gathering in time and space, of making lines that do not reproduce what we follow, but instead create new textures on the ground. As I stated above, Ahmed didn’t provide a clear guide to coalition building. Queer people’s lives in this article look molecular and unrelated, maybe it’s because of the theoretical approach this article is taking, which cares more about the phenomenon and how bodies perceived them, not collective actions. However, I do think it will be helpful if phenomenologists analyze more temporal aspects, as Ahmed does in this article, pointing out the history and the future in the present. So that we could put the social process of world-making in the forefront, preventing the creation of an illusion that phenomenology is about how an unrelated person sitting in front of their desk and perceiving the world around them individually, as if no one existed in their world.

As we know, Sara Ahmed is a key figure in contemporary affect theory. I want to link her theory with theories from other affect theorists and try to make a dialogue between them. First, when being asked, Do we have hope now, Brian Massumi (2015: 1) said, the way that a concept like hope can be made useful is when it is not connected to an expected success - when it starts to be something different from optimism – because when you start trying to think ahead into the future from the present point, rationally there really isn’t much room for hope. If the hope is the opposite of pessimism, then there’s precious little to be had (2). However, if hope is separated from the concepts of optimism and pessimism, from a wishful projection of success or even some kind of rational calculation of outcomes, then he thinks it becomes interesting, because it places it in the present (2). Massumi continued: There’s always a sort of vagueness surrounding the situation, an uncertainty about where you might be able to go and what you might be able to do once you exit that particular context. This uncertainty can actually be empowering – once you realize that it gives you a margin of maneuverability and you focus on that, rather than on projecting success or failure. It gives you the feeling that there is always an opening to experiment, to try and see. This brings a sense of potential to the situation. …You are only ever in the present in passing. If you look at it that way, you don’t have to feel boxed in, no matter what horrors are afield and no matter what, rationally, you expect will come. You may not reach the end of the trail, but at least there’s a next step. The question of which next step to take is a lot less intimidating than how to reach a far-off goal in a distant future where all our problems will finally be solved (3).

Highlighting the potential of uncertainty and the maneuverability of every moment are the shared ideas of Ahmed and Massumi, even though they discuss these topics from different trajectories. Massumi situated his philosophical thoughts within the tradition of process philosophy, which emphasizes ontogenesis (becoming) rather than ontology (being). Incidentally, most feminist thoughts after Beauvoir take up the fundamental standpoint that women, heterosexuality, or gender is something “becoming,” not “being.” At this point, feminist theories align with process philosophy, shedding light on the process of “becoming.” Becoming is where power was maneuvered, but also where hopes and agency emerged. We can tell it from the discussion above. If you’re not in the straight line, surprises will arise. As Eve Sedgwick (1997: 22) highlighted, there are good surprises and terrible surprises. It’s a waste if we keep ourselves in a state of paranoia only because we don’t want to face any surprises. Hopes are from the reparative reading, which acknowledges that the future may be different from the present. Hence, it’s not only paranoid but also effortless to eliminate bad surprises. If we were to continue Ahmed’s theory, once you’re out of the straight line, things become uncanny and disconcerting. What we could do, along with Massumi’s ideas, is try to navigate our movements. Navigation is a valuable concept, as it can be linked to Ahmed’s discussion of orientation. At every moment, we’re navigating ourselves toward a particular orientation. Along the road, we might be reoriented toward the straight line; we might feel out of place since our bodies are oblique when we’re in the line; we might then decide to open ourselves to look back, get lost, and try to find our way again. This is the process of navigation. And what’s important is not whether we’re along with the queer line, but what our orientation would be? How can we do when things become oblique or slip away? Where could we find support? Through the navigation, we find hope. As Massumi stated, we may not reach the end of the trail, but at least there’s a next step. Along the trail, we have already felt hope since the line has taken a surprising form, whether it’s a good surprise or a bad one.

Reference

Ahmed, Sara. 2006. “Orientations: Toward a Queer Phenomenology.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. 12(4): 543-574.

Butler, Judith. 1990. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York and London: Routledge.

Cohen, Cathy J. 1997. “Punks, Bulldaggers, and Welfare Queens: The Radical Potential of Queer Politics?” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. 3: 437-465.

de Beauvoir, Simone. 1949/1953. “Introduction.” In her book The Second Sex. Translated and edited by H. M. Parshley. London: Jonathan Cape.

Haraway, Donna. 1988. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” In Carloe R. McCann, Seung-kyung Kim, and Emek Ergun (edited). 2021. Feminist Theory Reader: Local and Global Perspectives. (fifth edition) New York and London: Routledge. pp. 303-310.

MacKinnon, Catherine A. 1989. Toward a Feminist Theory of the State. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Massumi, Brian. 2015. Politics of Affect. Cambridge and Malden: Polity Press.

Sedgwick, Eve. 1997. “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading; or, You’re So Paranoid, You Probably Think This Introduction is About You.” In her book Novel Gazing: Queer Readings in Fiction. Durham: Duke University Press.

Spivak, Gayatri. 1988/1993. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” in Patrick Williams and Laura Chrisman (eds.) Colonial Discourse and Post-colonial Theory: A Reader. London and New York: Routledge. Pp. 66-111.

The Combahee River Collective. 1977. The Combahee River Collective Statement. In Breanne Fahs. 2020. Burn It Down! Feminist Manifestos for the Revolution. Brooklyn and London: Verso. Pp. 271-280.

West, Candace, and Don H. Zimmerman. 1987. “Doing Gender.” Gender and Society. 1(2): 125-151.